|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

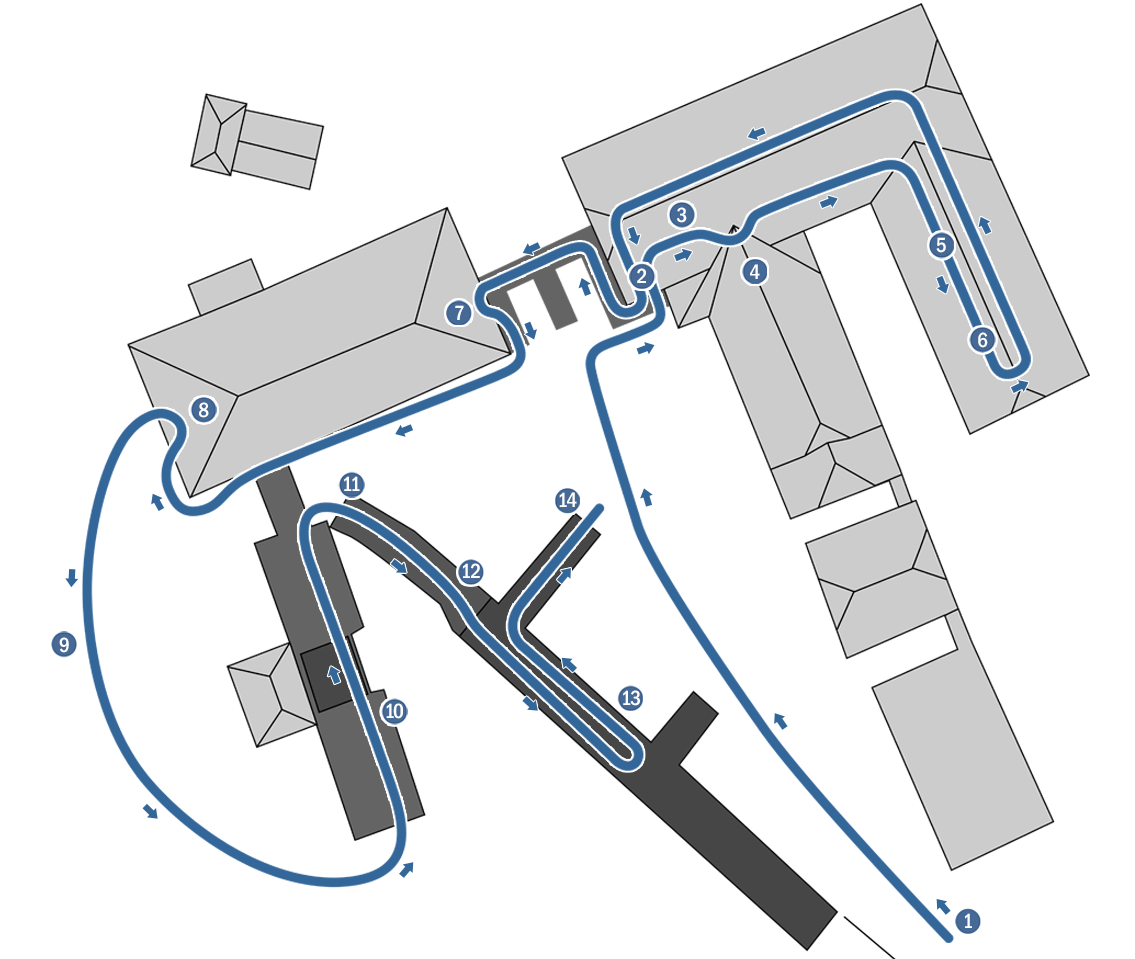

Welcome to this accessible and guided tour around the Pozo Julia Mining Complex.

Over the path that we propose to you, you'll be able to learn about the past and present of this mining complex firsthand from its main players, venturing inside some of the different buildings that make up the mine.

On the signage that marks the beginning of the route, you will find information on the journey that you are about to undertake and on the history of Pozo Julia.

At each visitable area (as well as from this website), you can download an audio guide that will give you information on the workings and use of representative spaces such as the lamp room, the compressor room, and the headframe –amongst others– while also learning about the work of the driller, the pickaxe miner, and the pit prop installer.

As you may have seen, there is an audio guide for children, as well as a sign language guide for those with hearing disabilities.

We'd like to take this opportunity to thank you for your visit, and we hope that this trip to our recent past allows you to share with us our appreciation and love for a mine that was –at one time– the past, present, and future of this municipality. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Belonging to the company Antracitas de Fabero, the construction of the Pozo Julia mining shaft started in the year 1947. This three-story vertical shaft that reaches 275 meters in depth was accessed through a headframe with an elevator to transport both people and mining shuttle cars, and the image of said headframe and elevator is now the most identifiable of the mining complex.

It was in this mining shaft, in 1962, that the brush-based winning machine was first used in Spain, a modern piece of machinery for extracting coal that increased yields and reduced the number of staff needed while also representing a technological breakthrough in the mining sector.

Still, coal reserves were gradually being depleted. The Pozo Julia Shaft closed in 1991 and Antracitas de Fabero had to lay workers off. A year later, the mines were forced to close completely or to be restructured. Later, in 2007 and under the direction of UMINSA, the facilities at the Pozo Julia Mining Shaft fell into the hands of the City Hall of Fabero. The City Hall decided to turn the mining shaft into a space to showcase the realities of a mining industry that was, at one time, momentous for the Fabero Watershed. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

The lamp room is where the miners picked up their lamps, which had been previously charged in preparation for the long day's work in those dark galleries.

As time passed and technology got better, carbide lamps gave way to electric lamps and helmets with modern lights, so as to allow the miner to move about more freely.

The task of the "lamp man" was to distribute carbide to the miners and, in more recent times, to use the chargers that you can see inside the room to keep the electric lights charged at all times.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

The shower area is just in front of you, which is where the miners cleaned themselves up after their long day of work – once they had hung up their wet, coal-dust-laden clothing on the hangers in the changing room.

This space has individual and collective showers where between 100 and 150 miners would shower at any given time.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

The watchmen were in charge of making sure that the work got done correctly, and of keeping track of the progress made by the pickaxe miners, drillers, and pit prop installers, who were paid by the amount of progress they made and not by the hour.

The watchman, who was typically a worker who was exceptional at his job, enjoyed a status that was different from that of the common miner, as he had his own area separate from that of the miners. The rest of the staff were not allowed to enter into the watchmen’s area.

The main difference when compared with the miners' area was that there were individual showers which were separate from those of the rest of the staff and there were sinks with mirrors. Likewise, the watchmen’s area was much better equipped and cared for than the one used by the other miners. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Experts were typically technical mining engineers and were at a higher level in the command chain, above the watchmen. Thus, they received special benefits like an individual shower and locker with a separate access door. The experts did not put their dirty clothing on the typical hooks; instead, an employee came by to pick it up, wash it, and hang it in their lockers.

The experts' work did not involve monitoring the workers, which was the job of the watchmen, but instead they were responsible for ensuring the proper general operations of the mine and making any pertinent decisions after having considered all the different jobs being done. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

The compressor room is one of the most important spaces of any mining complex.

In the case of this mine, the compressor room has three large compressors with American motors and British machinery that came to Pozo Julia in the 1960s.

These compressors generated the compressed air that was needed for the great majority of the tools to work both inside and outside of the mine.

This setup's size was incredible as the compressed air, pumped through lines, had to get to all the mine's corners. Two employees worked here: the person in charge of the room and the electrician, as these large compressors needed a reliable source of electricity that would provide them with a high level of electrical power. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

The machinery that still remains in this room was responsible for raising and lowering the transport cages that were found inside the headframe, creating a type of mining elevator that was used in vertical shafts like this one to raise and lower materials, miners, and shuttle cars full of coal extracted from the depths.

The machine room operator was the employee who stopped the transport cage at the correct spot, just at the entrance of the different galleries that this enormous mine had; therefore, he had a great deal of responsibility. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Opposite the machine room, full of tracks for the shuttle cars, was the space where all the materials that would be used inside the mine were stored.

A slight slope allowed the shuttle cars to move about easily atop the rails from the transport cages to the classifying area, where the shuttle cars' contents was unloaded into large hoppers. After initial selection, the coal went by conveyor belt to the washing facility, the building that is in front of you, where it was classified by size. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

The headframe housed the pulley system which allowed the coal to be taken out of the mine and which brought the miners to the deepest depths of the mine – all thanks to the transport cage.

Currently, you can hear the water that has flooded the hundreds of meters of galleries that the mine was made up of. When the mine was in operation, this water was extracted from inside by means of a pumping system that was located at the deepest part of the shaft. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

The driller was responsible for perforating the stone with his jackhammer and filling the holes made in the stone with explosives so as to blast out sections of rock and progress through the gallery.

After the explosion, the timbermen were in charge of putting the frames in place – wood and iron structures designed to keep the roof and walls from caving in and more debris from falling.

This stop on the itinerary is at what is known as an extraction site – the place where this work was undertaken by the drillers and timbermen. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

The pickaxe miner was the person in charge of getting the coal out of the veins. Located in a narrow pit, the pickaxe miner used a type of pneumatic drill to extract the coal, which was then taken to the general gallery by means of a special conveyor belt. From there, the shuttle cars were filled with coal and sent out of the mine.

The job of a pickaxe miner was one of the hardest and most dangerous of the entire mine. Debris, the conveyor belt, and the pneumatic drill all brought about illnesses related with bone and joint wear and tear, osteonecrosis, hearing loss, and –above all– silicosis, an illness produced by the silica in the rock, which dries out the miner's lungs and can cause death in advanced cases. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

The brush-based winning machine, introduced at Pozo Julia in the 1960s, was an extraction system that had two motors in charge of moving about a large mass of iron with blades at its ends. The brush, which constantly swept near the vein, collected the loose coal and sent it onwards to the conveyor belt where it was, in turn, sent to the general gallery.

The pit prop installers were in charge of propping up the roof that the brush created in the pit and moving the system along the vein once the area was opened up.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Solidarity between miners is one of the most evident aspects of this hard and dangerous job. The advances and improvements gained in terms of working conditions, and based on the strength of said miner solidarity, have been –throughout our recent history– something that has ended up benefiting all workers. These benefits are the result of long struggles for mining workers' rights, struggles in which the women and inhabitants of these mining villages actively participated.

Said struggles still last today, aimed at keeping the history of our people from disappearing, providing those who are interested with a glimpse into a reality that has gone down in history as an integral part of our culture. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|